My friend Maddie said it might be a good idea if we wrote about songs and shared our writing with each other. I said yes, good idea, and so we did.

Here is what I wrote, and here is what she wrote. I think we’ll keep doing this, each month picking a song and writing about it, and perhaps posting and perhaps not. In any case, I recommend sharing what you love with those you love and trying to explain yourself.

What follows is incomplete and branches off wildly without resolution, I apologise, but here it is, anyway.

In the worship songs I grew up singing, there is no room for impatience. There is, on the other hand, plenty of room for self-flagellation and prostration. You praise by comparison. Here are the things you cannot or are not. There is your god, who can, who is, who will. Bring me closer; make me better — that’s what you sing.

In every one of those songs there is an interminable bridge, long enough for confession, repentance, or transcendence. The band cycles through chords one, five, four, one, and your hands are up in the air, if you’re doing it properly, even if you’re shy. My hands were up in the air, sure, my eyes were closed almost all the way. But not before I’d seen enough other people doing it first.

You wouldn’t really sing, ‘But it takes so long, my Lord’. There isn’t room for this kind of caveat.

-

It was winter in Syracuse and I was alone. Christmas was over, and so were the celebrations of the new year; my roommate was still out of state with her family, and my partner had left on the bus back to New York City, and I had tidied the flat and wrapped in foil the remainder of the Happy New Year cake, fine-crumb vanilla sponge pocked with holes where the candles had been, and I had pulled the blinds tight against the hundred-year-old windows, and I went to bed by myself.

How could I go on outside of organised fun, now that nobody anymore had my whereabouts at the front of their mind? How to relax my arms and face, tense with efforts towards jolliness? So that I could go to sleep and wake up safely, with nobody to hold or look at, I first had to plug myself into the current of the world.

I started looking at the internet on my phone. That’s how I found the song: at around one in the morning, in the dark, a tiny square on someone’s Instagram story reminded me of the solo work of George Harrison.

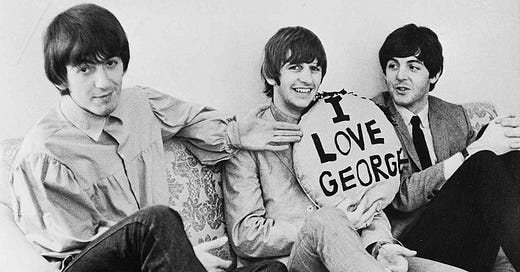

I had loved the Beatles since I was tiny; they were, I thought, what every band was aiming to be. I considered all four of them my dads, sort of. And I was particularly fond of George. His long, narrow face with its heavy brow, its serious eyes, reminded me of my father’s face, or at least of my father’s face when it was young, which I didn’t know firsthand — I remember him in his forties, slightly rounder and softer — but from the photos I loved to look at, the photos my mother took of him around the time they met. A face of a boy, really. And George’s preoccupation with God seemed to match my father’s. Both men wrote songs to their divinity and played them on their guitars.

Be generous to me. Sometimes a set of broad similarities can be considered a profound connection, particularly if the two guys had the same teeth and are both dead.

Alone and not really at home, I saw the album cover of George in gumboots in a field and I wanted to listen to him again. I went searching for a kick of familiarity. But I couldn’t get past the most famous track of his most famous album.

‘My Sweet Lord.’ A set of hallelujahs and another: I knew this song, I had heard it a long time ago. I could fall asleep.

-

‘My Sweet Lord’ is two sets of two chords and that’s it for the whole song. Imagine a pair of dancers only swaying: one foot to the other then back, settled deep in the music, almost unbothered by it, attached to each other gently, without tension, not pulling, not leading, in search of no destination. There is a shining moment, a harmonic arrival, when George lands on the tonic to sing the start of the chorus: ‘I really want to see you’. But soon you’re back out the other side of that satisfaction, into the onwards onwards, knocked from the sublime arrival by the complaint: ‘But it takes so long, my Lord.’

George’s song is petulantly, bizarrely cheerful, shimmering with that lurid jangly sound that people always refer to as ‘George Harrison’s signature slide guitar’, and then there’s the chanting. George wanted people to get on board with the praise of it all before they even realised they were singing the Hare Krishna mantra. I can imagine him saying, ‘It’s all the same god, man.’

The song feels optimistic, unaware of its own weight. I don’t know if I hear that in many songs, or many new songs, at least. But perhaps it’s just that old trick that gets me every time: nostalgia doing its good work of sweetening into bliss what is likely quite banal.

The song ends by fading, which means it can never end. Why doesn’t every song fade out? Why wouldn’t you choose that, if you were making a song? Why would you want the ending. Why would you want the answer.

-

When I was small and awake in the night, I used to pray. Out of terror, I think, and never for anything specific: just to stay alive, to be better at living. I would pray, furiously, to be good and worthy, suspecting in the dark that I could not be good or worthy without divine help.

When I decided I didn’t believe in whatever God was — which actually didn’t really happen like other things happen, I didn’t think about it and decide, ‘No more of that’; it’s more like I realised after the fact, like at some point in my mid-teens I had left God behind and didn’t notice — but in any case, when I decided or realised or had walked far enough away from God, a loneliness opened up in me that was different from the loneliness of missing other people or the loneliness of being misunderstood.

No, that’s not right. I think that loneliness was there all along. It’s what I was talking to when I was talking to my god. I think it’s what I write to now: a listener who can’t exist. And I still find myself praying, sometimes, when I am desperate. I will lie in the dark and whisper to nothing, Please, please.

-

I listened to ‘My Sweet Lord’ several times a day that winter. This song that said nothing about loneliness or being lost, a song that had nothing to do with me, really… Well, it cheered me up.

Then spring came, and there were people around again for me to talk to, and the windows could be opened for hours at a time, and I started to listen to new songs, different songs. I didn’t need the corny hymn to do its spirit-lifting work. But one evening, out for a cheap writing school dinner at a bicycle repair shop that doubled as a restaurant, the song came on — a song that had become a kind of secret to me — and it was like hearing someone calling my name. It was like hearing someone I loved, who had died a long time ago, calling my name.

Whole heart bursting, Soph

this is very beautiful and interesting buslt I must confess I was distracted by the idea of a bicycle repair restaurant